Charles Ives Biography - A Very Quick Guide

Artist:

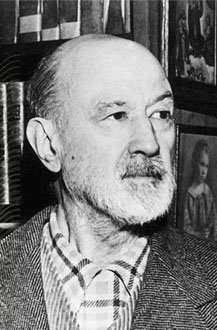

Charles Ives

Born:

October 20, 1874

Died:

May 19, 1954, New York

Charles Ives (1874–1954) was an American composer and insurance executive, born in Danbury, Connecticut, the son of a U.S. Army bandmaster. Taught music by his father from childhood, he later studied composition at Yale University with Horatio Parker. After graduating, Ives chose not to pursue a professional musical career, believing it might force him to compromise his artistic ideals. Instead, he entered the insurance business—eventually founding the firm Ives & Myrick—while continuing to compose in his spare time and working as an organist in several churches. He married Harmony Twitchell in 1908 and lived in New York for the rest of his life. After a series of heart attacks beginning in 1918, his composing activity declined sharply; his final work dates from 1925. Ives died in 1954, and his reputation has risen steadily since, making him one of the central figures in early American modernism.

Ives’ Music

Ives’ training at Yale grounded him in traditional 19th-century forms, but his imagination was shaped by his father’s band music, outdoor sounds, and experiments with tuning and layering. Many of his early songs and chamber pieces explore bitonality, polytonality, and complex rhythmic structures. His Variations on “America” (1891), originally for organ, shows both humour and early use of contrasting keys.

From 1908 onward he developed the experimental voice for which he is best known. The Unanswered Question (1908) introduced his signature technique of juxtaposed musical layers, combining quiet sustained strings, an isolated trumpet “question,” and increasingly agitated flute “answers.” His Concord Sonata (1909–15) reflects his fascination with New England Transcendentalism and includes quotations, dense harmonies and extended techniques such as tone clusters played with a piece of wood.

Ives’ most ambitious works include Symphony No. 4 (1910–16), requiring huge forces, multiple ensembles, quarter-tone tuning and extensive quotation—an exploration of philosophical ideas similar to those in The Unanswered Question. Several attempts to reconstruct his unfinished Universe Symphony have been made, though no version has entered standard performance.

Reception

During Ives’ lifetime, his music was rarely performed: its dissonance, rhythmic complexity and experimental scoring discouraged performers and audiences. Early champions included Henry Cowell, Elliott Carter and Nicolas Slonimsky. Wider recognition began in the 1940s, particularly after the 1946 premiere of Symphony No. 3, which won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize. Conductors such as Leopold Stokowski and later Michael Tilson Thomas helped bring the larger works to public attention.

Today Ives is regarded as a major “American original,” admired for his independence, integration of hymn tunes and popular melodies, and bold exploration of musical possibility. His music continues to divide opinion, praised for its imagination yet sometimes criticised as chaotic or uneven, but its influence on later American composers is undeniable.

Ives’ Music

Ives’ training at Yale grounded him in traditional 19th-century forms, but his imagination was shaped by his father’s band music, outdoor sounds, and experiments with tuning and layering. Many of his early songs and chamber pieces explore bitonality, polytonality, and complex rhythmic structures. His Variations on “America” (1891), originally for organ, shows both humour and early use of contrasting keys.

From 1908 onward he developed the experimental voice for which he is best known. The Unanswered Question (1908) introduced his signature technique of juxtaposed musical layers, combining quiet sustained strings, an isolated trumpet “question,” and increasingly agitated flute “answers.” His Concord Sonata (1909–15) reflects his fascination with New England Transcendentalism and includes quotations, dense harmonies and extended techniques such as tone clusters played with a piece of wood.

Ives’ most ambitious works include Symphony No. 4 (1910–16), requiring huge forces, multiple ensembles, quarter-tone tuning and extensive quotation—an exploration of philosophical ideas similar to those in The Unanswered Question. Several attempts to reconstruct his unfinished Universe Symphony have been made, though no version has entered standard performance.

Reception

During Ives’ lifetime, his music was rarely performed: its dissonance, rhythmic complexity and experimental scoring discouraged performers and audiences. Early champions included Henry Cowell, Elliott Carter and Nicolas Slonimsky. Wider recognition began in the 1940s, particularly after the 1946 premiere of Symphony No. 3, which won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize. Conductors such as Leopold Stokowski and later Michael Tilson Thomas helped bring the larger works to public attention.

Today Ives is regarded as a major “American original,” admired for his independence, integration of hymn tunes and popular melodies, and bold exploration of musical possibility. His music continues to divide opinion, praised for its imagination yet sometimes criticised as chaotic or uneven, but its influence on later American composers is undeniable.

Top Pieces on 8notes by Charles Ives