Miles Davis Biography - A Very Quick Guide

Miles Davis (May 26, 1926 – September 28, 1991) was an American jazz composer, trumpeter and multi-instrumentalist and was one of the most influential, innovative and original musicians of the twentieth century.

In terms of importance to the history of jazz, few knowledgeable critics would balk at describing him as an innovative genius with an unmistakable style and unmatched musical range. Stylistically, his vast catalogue encompasses bebop, cool jazz, modal jazz, and jazz-rock fusion. He was a pivotal figure in the evolution of the latter three. His recordings, along with the live performances of his many seminal bands, were vital in jazz's increased artistic acceptance. A popularizer as well as an innovator, Davis became famous for both his languid, melodic style and his laconic and at times confrontational personality. As an increasingly well-paid and fashionably-dressed jazz musician, Davis was a symbol of the music's commercial and artistic potential.

Davis is the latest, and perhaps the last, in the line of supremely innovative and influential jazz trumpeters that starts with Buddy Bolden and runs through Joe 'King' Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, and Dizzy Gillespie. Davis has been compared to Duke Ellington as a musical innovator. Both were skillful players on their instruments but were not considered technical virtuosos. Both expressed their musical ideas more as bandleaders, although Davis soloed much more than Ellington. Both tailored their compositions to the players in their bands.

| Contents |

Early life

Davis was born Miles Dewey Davis III into a relatively wealthy African-American family living in Alton, Illinois, being the son of Miles Davis II, a successful East St. Louis dentist. His mother Cleo, a capable pianist, wanted Miles to learn the violin but, for his thirteenth birthday, his father bought him a trumpet. Davis took to it immediately, and by age fifteen he was playing in public with bandleader Eddie Randall and studying under local trumpeter Elwood Buchanan. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato, and Davis would carry his clear signature tone throughout his career. This became a characteristic of the 'cool' sound, although Davis also pioneered the use of a metal mute, which to a degree supplied overtones similar to vibrato.

In 1945, after having graduated from high school and playing for a brief time with Charlie Parker in Billy Eckstine's band, he moved to New York City ostensibly to take up a scholarship at the Juilliard School of Music. In reality, however, he neglected his studies and immediately set about tracking down his heroes: amongst them Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Coleman Hawkins.

By 1948 he had served his apprenticeship as a sideman, both on stage and record, and a recording career of his own was beginning to blossom. Davis began to work with a nonet that featured then-unusual instrumentation such as french horn and tuba. The nonet featured a young Gerry Mulligan and Lee Konitz. After some gigs at New York's Royal Roost, Davis was signed by Capitol Records. The nonet released several singles in 1949 and 1950 featuring arrangements by Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan, and John Lewis. This began his collaboration with Evans, with whom he would collaborate on many of his major works over the next twenty years. The sides saw only limited release until 1957, when they were released as the album Birth of the Cool.

Playing in the jazz clubs of New York, Davis was in frequent contact with users and dealers of illegal drugs and by 1950, in common with many of his contemporaries, he had developed a serious heroin addiction, possibly aggravated by the lukewarm reception his first personal recordings had received. For the first part of that decade, although he gigged a great deal and played many sessions, they were mostly uninspired and it seemed that his talent was going to waste. No one was more aware of this than Davis himself, and in 1954 he returned to East St. Louis and, with the help and encouragement of his father, he kicked heroin, locking himself away from society until free of the drug.

First quintet

He returned to New York reinvigorated and formed the first great incarnation of the Miles Davis Quintet. This band featured a young John Coltrane (tenor saxophone) and, at times, such luminaries as Sonny Rollins (tenor saxophone) and Charles Mingus (double bass). Musically, the band picked up where Davis's late forties sessions left off. Eschewing the rhythmic and harmonic complexity of the prevalent bebop, Davis was allowed the space to play long, legato, and essentially melodic lines, in which he would begin to explore modal music, his lifelong obsession.

These records — Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet and the 1948 Birth Of The Cool — define the sound of so-called cool jazz, which would be one of the dominant trends in the music over the next decade and beyond.

While the rest of the musical establishment was still coming to terms with Davis's innovations, he himself had moved on. Reunited with Gil Evans, he recorded a series of albums of stunning variety and complexity, showing his mastery of his instrument in almost every musical context. The first, Miles Ahead (1957), showcased his playing with a traditional jazz big band and a driven horn section beautifully arranged by Evans. The pair tackled jazz tunes including Dave Brubeck's 'The Duke', as well as Leo Delibes' 'The Maids Of Cadiz', the first piece of European classical music Davis had recorded.

Milestones (1958) captured the sound of his current sextet, which now was composed of Davis, Coltrane, Julian 'Cannonball' Adderley (alto sax), Red Garland (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), and Philly Joe Jones (drums). Musically, it encompasses both the past and the future of jazz. Davis showed that he could play blues and bebop (ably assisted by 'Trane), but the centerpiece is the title track, a Davis composition centred on the Dorian and Aeolian modes and featuring the free improvisatory modal style that Davis would make his own. Later the same year Davis and Evans's free arrangement of George Gershwin's Porgy And Bess, the framework of Gershwin's tunes providing ample space for Davis to improvise, showing his mastery of variations and expansions of the original themes as well as his original melodic ideas.

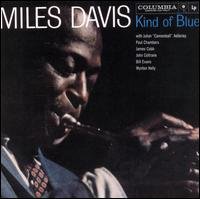

Kind of Blue

In March 1959 Davis re-entered the studio with a slightly new sextet, comprised of Coltrane, Adderley, Chambers, Jimmy Cobb (drums), and Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly alternating on piano, to record what is widely held as his masterpiece. Recorded in just two sessions, and improvised by the band about skeletal harmonic frameworks sketched by Davis and Evans, Kind Of Blue would revolutionise jazz. Freed from the rhythmic strictures that had driven his previous work, and masterfully supported by the band, Davis had sufficient space to expand his new harmonic and melodic ideas, and the sidemen proved themselves more than equal to the task. Amongst the best selling jazz albums of all time, and still widely hailed as the greatest, it seemed that Kind Of Blue had a lasting influence on every musician who heard it, jazz or otherwise, and it still stands as an equal to any of the world's pivotal musical works.

The same year, while taking a break outside the famous Birdland night club in New York City, Davis was beaten by the New York police and subsequently arrested. Believing the assault to have been racially motivated, he attempted to pursue the case in the courts, before eventually dropping the proceedings. Such treatment was markedly at odds from his treatment outside the US, and especially on his regular European tours, where he was fêted by society.

After an extensive tour behind Kind Of Blue, Davis took a break from his quintet. Looking for something different, he turned to arranger Gil Evans for help with his next work. Returning to their mutual interest in classical music, which had first borne fruit on Miles Ahead, Evans arranged a version of Joaquin Rodrigo's 'Concerto de Aranjuez' for Davis. Married to four other pieces, Rodrigo's work provided the centrepiece of Sketches Of Spain (1960).

Throughout the early 1960s Davis continued his prodigious output, undaunted by the loss of Coltrane to a solo career. His last contributions appeared on the 1961 album Someday My Prince Will Come, a collection often overlooked due to its legendary predecessors. Further fine studio recordings, such as Seven Steps To Heaven (1963) and My Funny Valentine (1964), were interspersed with further with live recordings (In Person (1961), At The Carnegie Hall (1962) and In Europe (1964)) featuring his evolving touring band.

Second quintet

By the time of ESP (1965) the lineup — Davis's second great quintet and the last of his acoustic bands — consisted of Wayne Shorter (saxophone), replacing George Coleman, Herbie Hancock (piano), Tony Williams (drums) and Ron Carter (bass). There followed a series of strong studio recordings: Miles Smiles (1966), Sorcerer (1967), Nefertiti (1967), Miles in the Sky (1968) and Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968). The quintet's approach to improvisation came to be known as 'time no changes,' because while they retained a steady pulse, they abandoned the chord-change based approach of bebop.

A two-night Chicago gig by this band is captured on the 8-CD set The Complete Live at The Plugged Nickel 1965 released in 1995.

Miles in the Sky and Filles de Kilimanjaro, on which electric bass, piano and guitar were tentatively introduced on some tracks, clearly pointed the way to the subsequent fusion phase in Davis's output. Davis also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records, and on Filles de Kilimanjaro, Dave Holland and Chick Corea replaced Carter and Hancock on some tracks. Davis also took over the compositional duties, which had been largely relegated to Shorter during the preceding years.

Fusion

Recent boxed sets have shown Miles's progression from the 'free-bop' of the Second Great Quintet to the dense, rhythmic world of fusion was much less abrupt than what it seemed initially when In a Silent Way followed Miles in the Sky. Miles's influences, widely attributed to the tastes of girlfriend Betty Mabry, were the late '60s acid, funk and rock heroes, namely Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown, and Jimi Hendrix. Slightly later, most prominently on 1972's On the Corner, the influence of modern composer Stockhausen became evident. This transition required that Davis and his band adapt to modern, electric instruments in both performance and the studio. Bitches Brew, for instance, is a case study in the use electronic effects, multi-tracking, tape loops, and other editing techniques.

By the time In A Silent Way was recorded in February 1969, Davis had augmented his standard quintet with additional players. Phenomenal talents such as Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett took turns along with Hancock in the studio, while the masterful Jack DeJohnette ably shared the drum chair with Tony Williams. While never an official member of the band, the young John McLaughlin made the first of his many appearances with Miles on the guitar. That record, and its successor, Bitches Brew, saw the first truly successful amalgamations of jazz with rock music, laying the groundwork for the genre that would become known simply as fusion. Both records, especially Bitches Brew, proved to be huge sellers for Davis, and he was accused of 'selling out' by many of his departing fans. While the sheer density and complexity of these albums, and what was to follow, defeat such accusations, Davis succeeded in expanding his fan base enough to propel Bitches Brew to the status of the greatest selling jazz record ever, while Davis himself moved into the larger, more lucrative, rock venues of his younger contemporaries.

Davis reached out to new audiences in other ways as well: From Bitches Brew, Davis's albums featured art typically much more in line with 'psychedelic' or black power movements than with his earlier albums' art. He took significant cuts in his usual performing fees in order to open for rock music groups like the Steve Miller Band and Santana. (Carlos Santana has stated that he should have opened concerts for Davis, rather than vice-versa.)

1970 saw Davis contribute extensively to the soundtrack of a documentary about the great African-American boxer Jack Johnson. A devotee of boxing, Davis drew parallels between Johnson, whose career had been defined by the fruitless search for a Great White Hope to dethrone him, and Davis's own career, in which he felt the establishment had prevented him from receiving the acclaim and rewards that were due him. The resulting album, 1971's A Tribute to Jack Johnson, contained two long pieces that used the talents of many musicians, some of whom were not credited on the record itself. These included guitarists John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock.

Working with producer Teo Macero, Davis created what many critics regard as his finest electric, rock-influenced album, and its use of editing and studio technology would be fully appreciated only upon the release of the five-CD The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions in 2003. Regardless, Davis refused to be confined by the expectation of his audience and continued to explore the possibilities of his new band. On The Corner (1972) showed a seemingly effortless grasp of funk without sacrificing the rhythmic, melodic and harmonic nuance that had been present throughout his entire career.

By the mid-'70s, his previous rate of production was falling. Get Up With It (1974) was a collection of outtakes and studio recording from the previous five years, which included 'He Loved Him Madly,' a fine tribute to Duke Ellington, as well as one of Davis's most lauded pieces from this era, 'Calypso Frelimo.' Contemporary critics complained that the album had rather too many underdeveloped ideas.

However, Davis's '70s recordings have in recent years undergone a fairly radical reassessment, and are now seen by many as a significant body of work comparable to that of his earlier periods, and as an extremely interesting mixture of ideas gleaned from jazz, funk and rock music as well as from experimental, 'process-oriented' European composers. Recently, Dave Douglas, Wadada Leo Smith, Mark Isham, Tim Hagans, Nicholas Payton and others have recorded albums more or less indebted to Davis's electric era.

Excluding an assortment of live recordings, including Agartha, commonly cited among the richest works of this period, the mid-'70s saw Davis enter retirement. Troubled by chronic pain from years of physical abuse, a serious kidney complaint, diabetes, a renewed dependence on heroin and cocaine and again at odds with the law, Davis withdrew almost completely from the public eye.

While convalescing, Davis saw the fusion music that he had spearheaded over the past decade firmly entered the mainstream. Whether played by Davis's many protégés, including Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra, or bands such as Weather Report, Davis's influence could be heard everywhere, as it could after each of his previous revolutionary advances.

Davis absented himself from the music industry for five years. For much of the early part he was seriously ill, but by the beginning of the 1980s he was back in good health and ready to assemble a new band.

Return to performance

As ever, Miles assembled his bands from among the finest musicians available, including the saxophonist Bill Evans (no relation to the pianist) and a young bass player called Marcus Miller, who would become one of his most regular collaborators through the decade. The first studio album The Man With The Horn (1981) was relatively poorly received. The same year, Davis prepared to tour again and formed a touring band largely different from those who'd played on the album. In May they played two dates as part of the Newport Jazz Festival and the concerts, and the live recording We Want Miles from the ensuing tour, were well reviewed.

By the time of Star People (1983) his band included John Scofield on guitar, with whom Davis worked closely on both that record and 1984's Decoy, an underdeveloped, experimental mixture of soul music and electronica. Despite the mixed quality of much of his recorded output, live Davis was still capable of moments, and entire concerts, of great inspiration. With a seven piece band, including Scofield, Evans, drummer Al Foster and bassist Darryl Jones (later of The Rolling Stones), he played a series of European gigs to rapturous receptions. While in Europe he took part in the recording of Aura, an orchestral tribute to Davis composed by the Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg.

Back in the studio, You're Under Arrest (1985) included another stylistic detour; interpretations of contemporary pop songs in Cyndi Lauper's 'Time After Time' and Michael Jackson's 'Human Nature,' for which he would receive much criticism in the jazz press, although the record was otherwise well-reviewed. Davis also noted that many accepted jazz standards were in fact pop songs from Broadway theatre, and that he was simply selecting more recent examples of pop songs to perform. You're Under Arrest would also be Davis's final album for Columbia, due to the long-term deterioration of his relationship with the label.

Having first taken part in the Artists United Against Apartheid recording, Davis signed with Warner Brothers records, and reunited with Marcus Miller. The resulting record, 1986's Tutu, would be his first to feature modern studio tools — programmed synthesisers, samples and drum loops — to create an entirely new setting for Davis's playing. Ecstatically reviewed on its release, the album would frequently be described as a modern version of the classic Sketches Of Spain, and won a Grammy award in 1987.

He followed Tutu with the soundtracks to two movies, Street Smart and Siesta, with neither the films nor Davis's scores being particularly noteworthy (other than Morgan Freeman's celebrated turn as 'Fast Black' in Street Smart), but he continued to tour with a band of constantly rotating personnel and his critical stock at a level higher than it had been for fifteen years.

Miles Davis continued to tour and perform regularly through the last years of his life, before succumbing to a stroke in September 1991 at the age of 65. He is interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York.

He was married to actress Cicely Tyson in 1981, and they were divorced in 1988.

Quotation

- In 1987 Davis attended a reception in honor of Ray Charles at Ronald Reagan's White House. A Washington society lady, seated next to him, asked him what he had done to be invited. 'Well,' Davis replied, 'I've changed music four or five times. What have you done of any importance other than be white?'

Samples

- Download sample of 'Boplicity'

Major discography

- Birth of the Cool (1948)

- Miles Ahead (1957)

- Milestones (1958)

- Kind of Blue (1959)

- Sketches Of Spain (1960)

- In Person (1961)

- At The Carnegie Hall (1962)

- Seven Steps To Heaven (1963)

- My Funny Valentine (1964)

- In Europe (1964)

- Miles Smiles (1966)

- Sorcerer (1967)

- Nefertiti (1967)

- Miles in the Sky (1968)

- Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968)

- In A Silent Way (1969)

- Bitches Brew (1969)

- A Tribute to Jack Johnson (1971)

- On The Corner (1972)

- Get Up With It (1974)

- The Man With The Horn (1981)

- Star People (1983)

- You're Under Arrest (1985)

- Tutu (1986)

- Doo-Bop (1992)

External links

- Miles Davis Discography (http://www.plosin.com/milesAhead/DiscoDetails.aspx)

- Sons of Miles: Interviews and profiles with Miles Davis and musicians influenced by him (http://www.culturekiosque.com/jazz/miles/rhemiles1.htm)

Recommended reading

- Milestones: The Music and Times of Miles Davis — Jack Chambers (ISBN 0-306-80849-8)

- Miles: The Autobiography with Quincy Troupe (ISBN 0-671-63504-2)

- Miles Davis — Ian Carr. The definitive, exhaustively researched biography (ISBN 0006530265)

Top Pieces on 8notes by Miles Davis